Adding Horses to your Game: Tips, Resources, Do’s and Don’ts

On The Mane Quest, I talk a lot about horse games, meaning games that are focused on riding, training, breeding or taking care of horses. Outside of the horse game niche however, there are plenty of games that feature horses as mounts, without them dominating the entire gameplay loop.

This article is aimed at game developers who want to include horses in their games without making the same couple of basic mistakes that make equestrians cry.

I’m trying to keep this text as accessible as possible for people without prior knowledge of horses and equestrianism, which in turn may make it seem a tad shallow for those of you who have that knowledge. The intention is to give game creators a starting point for further research and some ideas for how to add a bit of depth, variety and authenticity to their portrayal of horses.

If you’re making a game and planning to feature horses in some way, this article is for you. If you want to make a game about horses in some way but aren’t sure what that could look like, I highly recommend taking a look at my Horse Games That Should Exist articles:

Companions, Collectibles or Characters?

When deciding to add a horse or multiple to your game, you first need to make a conscious choice as to whether you are adding one single horse as the main character’s companion – as we see e.g. in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, Ghost of Tsushima or Shadow of the Colossus – or if you want the player to ride and own various horses and possibly replace them for better stats and cooler looks, like we see in Red Dead Redemption II, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

For a deep dive into the advantages and disadvantages of both formats, check out this article:

There isn’t a better or worse for this choice, it is simply a matter of what fits your game the best. But it should always be a choice consciously made, so you can make the most out of it and not get stuck in an awkward in-between. (looking at you, Assassin’s Creed 3)

One detail that I often see games miss out on is using names and gendered pronouns for horses: This is especially applicable for “Companion” horses where the player rides one specific horse for the whole game, but it can also be applied to several horses, with in-game text updating accordingly. There are cultures where naming horses is less common, but very generally speaking, your players will get more attached to an NPC if it has a name – make your horse(s) feel like a character instead of an object. This extends to pronouns: People who rides horses won’t usually use “it” to refer to a specific steed. A horse’s sex – stallion for intact males, gelding for castrated males, mare for females – is quite obviously visible at a glance under its belly, and we then use he or she to refer to the animal.

In Horse Tales: Emerald Valley Ranch, UI elements and dialogues use the gender of the actual horse you’re riding at that moment.

Ghost of Tsushima lets the player select one of three voice acted names for the horse they choose.

A Note on Realism and Practicality

Many horse loving gamers will tell you they want more “realistic” horses in video games. That can mean a huge range of things though, and not all of them will suit every type of game. In Game Design, we are always finding a balance between representing a thing with some amount of believability and authenticity, while making sure that the thing remains fun to do.

Every decision on how to make horses more realistic or lifelike should go hand in hand with asking yourself how said decision impacts gameplay fun and understandability. With that in mind, there are so many attainable ways to make horses in games seem a bit more lifelike and realistic while adding to player enjoyment.

Interactions: Pet, Feed, Care

Giving players ways to interact with their horse beyond “mount/dismount” can go a long way towards making the horse seem more like a living animal rather than a meaty motorcycle. While I generally don’t recommend adding horse care minigames in the way we know and often loathe them from horse games, giving horses a food or hygiene stat that the player occasionally needs to care for can add a bit of mechanical depth to what would otherwise only be a speed power up. But even interactions that are added solely for “fluff” can add a lot of value and a feeling of polish to your game – just have a look at how many people love Can You Pet the Dog.

So, what kinds of interaction make sense with a horse?

Horses tend to stretch out their neck and look silly when they’re getting scratched in good itchy spots. Fernhoof Grove represents this in its brushing minigame.

Elden Ring gives players the option to feed raisins to their magic goat horse companion to recover his health.

Pet or scratch: most horses are fine with having their neck stroked or patted, but some get really into it if you scratch their croup or their withers. They even make a wonderfully goofy face if you find the spot.

Feed: If your game already features collectible items and an inventory, this is a no-brainer. Let players pick up or buy apples, carrots, bananas, celery sticks, strawberries, grapes and watermelon slices to feed to their mounts. Maybe that gives the horse a speed bonus for a few minutes, maybe it heals the horse’s hitpoints, or maybe it’s just for fun and cuteness.

Soothe: Horses are prey animals and easily spooked. Perhaps nearby combat or vehicles give your horse a “Scared” condition that makes it harder to control, and your player needs to provide scritches and some kind words in order to manage. This of course needs smart balancing and good user feedback, because losing control over your mount can get frustrating very quickly otherwise.

Groom/Brush: In real life, we groom horses before putting a saddle on them to make sure there are no points of pressure or friction caused by crusted mud or hairs standing on end. Grooming your horse all over is also a great way to check for injuries and to familiarize yourself with what your horse “normally” looks and feels like so you’ll be sure to notice when anything’s off. I highly recommend letting players take off their saddle (or at least disabling it visually) when a grooming interaction takes place!

Check and pick hooves: Rocks and pebbles can get stuck in horses’ hooves and if they keep walking on them, that can lead to injuries such as hoof abscess. Perhaps checking and cleaning a horse’s hooves is an interaction the player character can occasionally do to prevent such problems.

There’s loads of options for making these interactions meaningful in gameplay, if that suits your game. But caretaking interactions can make horses feel more lifelike even if there are no serious consequences for not doing it. Making the player engage in such actions too frequently can definitely turn tedious and ruin the joy of it, so this requires a certain balance.

The Witcher’s Roach has a fear level. Geralt can calm her using magic, but a few scratches and soothing words would work just as well.

Red Dead Redemption 2 lets you groom your horse… but only next to the saddle, which is a bit goofy.

Animations and Gaits

Animating horses is not a simple task. Any quadruped animation is an additional challenge compared to two-legged creatures, and horses add further complexity by having particularly long legs with a lot of well-visible joints.

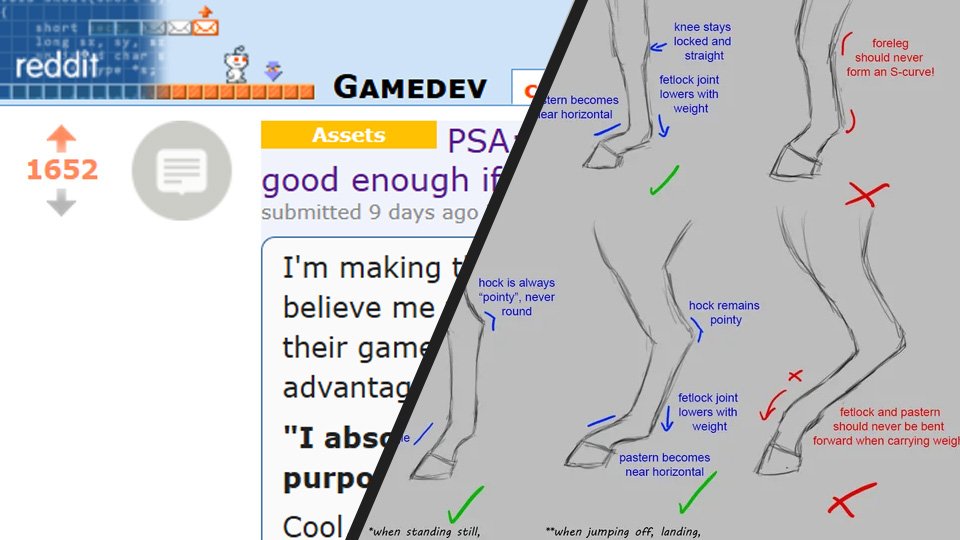

It’s no wonder that many developers with limited animation budgets go for the popular game-ready animation pack Horse Animset Pro (HAP) by Malbers. Unfortunately, HAP comes with a whole bunch of issues, from a horse realism perspective: While the basic gaits are correct nowadays, the pack’s animations often feature two bent forelegs at the same time while walking or trotting, which is impossible for a real horse and gives the whole animation a certain “two guys in a horse costume” look. Other game horses (that likely don’t use the same asset pack) such as Torrent in Elden Ring, Jin’s horse in Ghost of Tsushima and the mounts in My Time at Sandrock have similar issues due to how their inverse kinematics are set up.

Key Takeaways:

If you want horse lovers to really like your game, HAP isn’t good enough, plan for custom animations.

If HAP is your only option for budget or engine reasons, avoid using the Rear/Neigh animation and the Idle Look animation, they’re two of the worst offenders in my opinion. You can preview all of the animations here on Sketchfab.

If you’re working with Unreal Engine, you might be able to use the Horse Herd or Real Time Horse assets instead, which have significantly better animations. I cannot vouch for these assets’ usability however, and they unfortunately have fewer animations all in all.

When setting up inverse kinematics for horses on uneven ground, try to ensure that weight-bearing forelegs are never bent

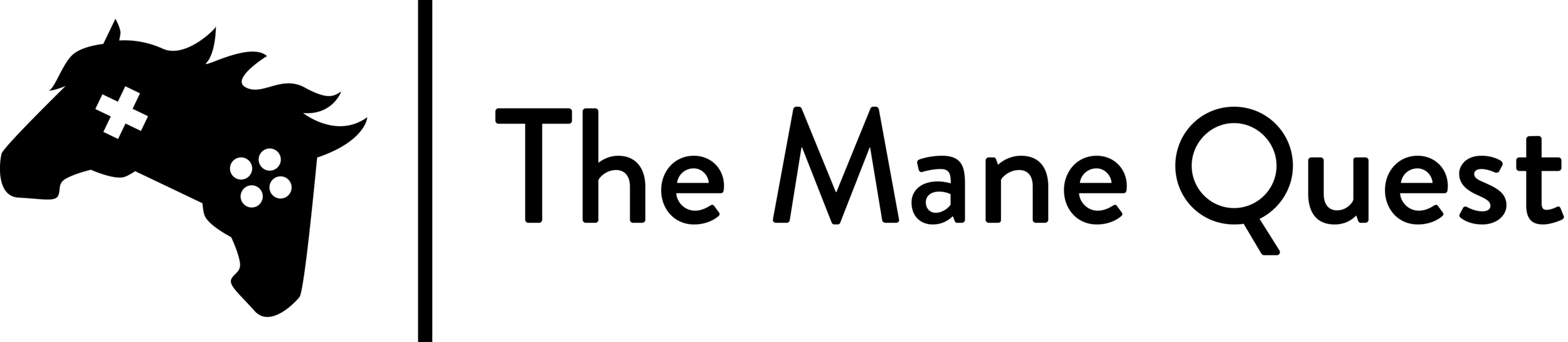

If you make your own horse animation, I recommend using Eadweard Muybridge’s photo sequences as references for basic gaits. Yes, the very first movie ever made is actually still an incredibly solid bit of reference footage for horse locomotion.

Use reference footage for everything, animating a horse well from memory is practically impossible. If you struggle to find reference footage for a specific motion you need, ask me or the TMQ community.

Have a look at this tweet as well as this thread for some common errors in depicting horse motion.

For more reference material for horse animation, check out this post:

Controls and Camera

The horse’s gaits: I recommend separate animations for each gait, and giving the player control over which gait they are moving at. (image source)

It is a pet peeve of mine – one of the 8 Horse Mistakes I want Game Developers to Stop Making – when games do not give me precise control over whether my horse is going at a walk, trot or canter. A horse’s movement is defined not only by how quickly it moves its legs, but also by the pattern it moves its legs in, i.e. what we call a gait.

Some games include mounts very exclusively as a speed upgrade in fast-paced gameplay and the only speed you’ll ever need is “as fast as possible”. Blizzard’s Heroes of the Storm is one such example. In it, horses move at a gallop or not at all, and that’s entirely good enough for a fast-paced MOBA where you barely have time to look at your character model anyway.

The first Windstorm game has many flaws, but one thing it does well is let you move at a specific gait and showing you which one you’re at.

Games that feature exploration and large open worlds are a different matter though: In those, I want to control the speed in which my horse moves. I may want to take my time riding across a beautiful landscape while admiring the environment, for example, that’s just a part of what I enjoy about playing games that feature traversal as a key mechanic.

While real-life horses have a lot of speed variety within a single gait – one horse’s extended trot can be faster than another horse’s collected canter – the simplest solution is to tie gait and speed together and think of walk, trot, canter and gallop as four preset movement speeds.

This is the best picture I could take of my horse and character in Horse Club Adventures because the camera is so limiting that I couldn’t get the whole horse in frame.

The Red Dead Redemption games as well as The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild do this well by giving you precise control over going a gait up or a gait down from your current speed. Bad examples on the other hand – this includes recent Assassin’s Creed games as far as I’m aware, as well as Ghost of Tsushima – require the player to focus on pushing a joystick only slightly if they want to move at anything slower than a canter. Some of them then even blend between the walk and trot animation, resulting in weird in-betweens. Do not blend between different gaits, or between different canter leads if you’re distinguishing those. Transitions between gaits should always be crisp, regardless of whether you’re portraying a trained and ridden equine or a wild one.

When it comes to the do’s and don’ts of implementing a good horse riding camera, my number one pet peeve is when games don’t actually let me simply watch my horse from the side while moving. People who like horses take a visceral joy in watching them move, and having a camera that limits the player’s view too much can be very frustrating.

Broadly speaking, horses are also a great subject for an ingame photo mode, and if you let players take pretty screenshots of their mounts in their full glory, you have a good chance to benefit from word of mouth marketing as horse loving players will be happy to share their nice horse pictures.

Terminology: Coats and Breeds

It’s entirely possible to include a horse in a game without breed and coat terminology becoming relevant, but I’ve just seen it done wrong too many times. If you call a grey horse white or call a horse brown without knowing the difference between a bay and a chestnut, many of your players might not notice or care, but you are demonstrating a lack of very basic horse knowledge. So if you label horse colors in your game, take a moment to ensure you’re labeling them correctly.

The question of “what do you call a horse of which color” unfortunately becomes complex very quickly, which is why it can be hard to give a beginner overview without misinformation. We put together a very basic guide for some common horse colors and what they’re called – this isn’t an exhaustive list, but if you need more detail or anything specific, I suggest you just write me an email honestly, because many “horse color guides” or simple search terms contain at least some small amount of wrong or outdated info.

Horse Breeds are fortunately a bit easier to research, but an individual horse breed’s characteristics may not be obvious to people without a trained eye. What’s worth knowing is that while there are many horse breeds that look similar to each other, there are also horse breeds that have a very distinct shape or color, such as Arabians with their dished faces and high tail carriage, Friesians and their high headset, lush manes and consistently black color, or Irish Cobs and their extensive feathering, heavy build and common Tobiano patterning.

Basic do’s and don’ts on Horse Breeds:

Finding and unlocking multiple horse breeds can be part of a game’s progress and achievements, like in Red Dead Redemption 2. (img src)

Picking a horse breed that fits your setting can make your game world feel grounded: cold environments usually make for stocky horses with thick winter coats, like this Fjord. (img src)

If you model a horse, it makes sense to pick a specific breed to base it on, so you don’t end up with an (unintentionally) unproportional horse with mixed characteristics. Thoroughbreds and Warmbloods are relatively “neutral” choices that will just read like “normal horse” to casual observers.

To get good side-view images of a horse’s body, google “[breed name] conformation”. Searching for and studying conformation guides for individual body parts will also help you avoid undesirable proportions and angles in your horse model.

If you include multiple breeds, be aware that adjustments to the model or color options may make sense in order to stay vaguely correct. You can usually find typical colors and other characteristics of a breed on its Wikipedia page.

If you want to include multiple breeds that all use the same model, you can get away with picking breeds that have similar characteristics. For example, many sporty warmblood breeds can’t be definitely distinguished from one another by visuals alone. You can also very easily make up new warmblood breeds if you have fictional countries to use as their origin.

It may make sense to pick a breed that specifically fits your setting, such as a Fjord or North Swedish Horse for a Scandinavian-inspired setting, or an Arabian or Akhal Teke for a desert environment – this applies for real-world settings as well as for fantasy environments inspired by these parts of the world.

Many modern horse breeds have only come into existence within the last two or three centuries, so if your game is set in e.g. medieval times, you might have to take a different approach. I can highly recommend the Wikipedia article for Horses in the Middle Ages as a starting point.

If you’re unsure, ask a horse person. The TMQ Communities are always happy to explain basic horse knowledge to well meaning but clueless game creators or writers.

Warmblood: A “Standard” horse so to say, widely used in sports like jumping and dressage (img src)

Arabian horse: note the slender build, slightly concave face and straight back. (img src)

Irish Cob: note the long, thick mane and tail, heavy build and hairy lower legs (img src)

Tack Items and Customization

Between modern equestrianism, historical settings or fantasy, the equipment that looks correct on a horse will vary quite a bit. Even so, you’ll mostly have the same handful of item categories: a saddle lying on some sort of pad or blanket, and a bridle with reins. Offering players different options for saddles, bridles, saddle pads and mane or tail styles for their horse is a relatively straightforward way to satisfy cosmetic variety and give people something to find and unlock.

A complete guide to tack items that exist and what they do would be impossible to fit into this article, so here’s a handful of basic tips:

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild offers a few saddle and bridle style customization options (img src)

In The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, customizing your horse’s mane and tail is only possible via a mod. This one got downloaded over 75’000 times.

Bridles tend to have a metal mouthpiece called a bit. There’s a lot of variety as to how horse-friendly or harsh these are, but the simplest and least controversial option is a snaffle bit, where the reins attach directly to the metal rings on the side of the horse’s mouth.

There are a lot of very cruel bits (from antique Indian thorn bits to twisted wires to extreme leverage and gag bits), that I’d recommend not portraying in games at all, if your protagonist is supposed to care for their horse.

Metal mouthpieces are widely used around the world, but they don’t need to be universal: There are bitless options that are generally kinder to a horse’s mouth – they instead work with pressure on the nasal bone. Check out a bosal, hackamore or sidepull bridle if that’s what you want to go for!

Modern saddles are generally distinguished into English and Western style saddles, each with further specialization depending on the discipline they’re used for. Generally speaking, they are made out of leather around a solid wood or metal frame called a saddle tree, and they lie on a cloth pad both to protect the leather from sweat as well as for increased comfort for the horse. The wikipedia page for saddles offers an excellent overview of a saddle’s parts and what they’ve looked like in different historical eras.

Tack can of course be stylized and simplified if that suits your game’s look, but I recommend keeping the basic shape of things. Good stylization is informed stylization, so you know which parts you can remove and which need to be there. Don’t leave away the saddle’s girth unless your saddle only consists of a handful of pixels, for example.

A horse’s long hair – the mane on its head and neck and the tail at the end of its spine – can be styled for aesthetics or practical reasons. Look up mane and tail braiding styles for a few examples, or consider options for different lengths from short-cropped to long and flowing.

In any case, I always recommend using concrete reference images for modelling your tack items, because if you make them up from imagination, you’ll very likely end up with something that’s either impossible or noticeably weird to an informed audience.

A standard Western bridle with a snaffle bit is a solid choice for a simple and ethical headpiece. (img src).

If you want to avoid putting metal in your horses’ mouths, a sidepull bridle can be a good alternative. (img src)

Horses at Home

If your game includes any sort of home base, daily rhythm or needs management for the player character itself, it makes a lot of sense to include your equine companion in those aspects as well. Of course, there are games where the main character never sleeps or has a place to rest, and that’s perfectly fine for video game logic and can extend to the player’s horse just as well.

But when the player character can go to bed, it makes a lot of sense for there to be a sense of rest for the horse too. This can be a conscious interaction for the player, e.g. they have to take off the horse’s saddle and put the animal into a paddock or barn for safekeeping during the night. It can also be a simple visual nod though: perhaps the cutscene that shows my avatar lying down on their bedroll includes a shot of an unsaddled horse grazing or dozing in the background. Ghost of Tsuhima got this almost right, but the fact that the horse lies down with its saddle on docks points.

I always find it quite jarring when I can put my horse home into its stable, but the horse then just stands there fully tacked up, as is the case in My Time at Sandrock or Stardew Valley.

Other animals you can have in My Time at Sandrock get to live in pens, but horses stand around in their saddles at all times.

What I’d like to see instead: horses grazing, relaxing, socializing while not wearing saddles or bridles. (img src)

In real life, taking off a horse’s tack and watching it go for a roll to scratch the sweaty spots on its back is just incredibly sweet and satisfying and I think some games could definitely profit from representing that moment too.

On another note: this deserves its own article at some point (edit: I wrote one! See here!), but remember that horses are herd animals and need space to move. If you include horse-husbandry at your player’s home, consider paddocks and pastures where horses can have the friends, freedom and forage that they need, instead of portraying horses kept alone in tiny stalls or tied up when not being ridden.

Sounds

This article is getting very long so I will keep this bit short: horses make a lot of different sounds, and they don’t neigh as much as movies would have you believe.

Loud neighing generally happens when horses call for each other from far away, perhaps when a horse approaches or leaves its stable and calls to its buddies, or when it sees a familiar horse out on the trail. Neighing comes with a movement of mouth, nostrils and flanks, so it requires a bit of animation in order to look fully convincing – movies create false expectations here, since film neighing is often overlaid over obviously still horses.

For the ambience of a stable, I’d recommend huffing breaths and sighs, the shuffling of hooves in straw, the crunch of hay being chewed and the occasional soft thud of manure hitting the ground, rather than relying on excessive neighing sounds.

Horses can also nicker, squeal, snort and even roar, depending on what they’re trying to communicate! I recommend having a look at this horse noise compilation or this horse noise guide before defaulting to whinnying sounds.

This image search is a perfect example for why this research can be a pain in the ass: apart from the top left result, these photos don’t actually show neighing, but yawning or flehmen. 🙃

Why the extra effort is worth it

Why does it make sense for game creators to go the extra mile when it comes to horse representation, when they could just as well do the bare minimum, like many are obviously already doing? Now obviously, I am biased as a horse lover: I want to see more games that get horses right and add features and details that elevate them from “there” to “lovable”.

However: putting a bit of extra effort into the depiction of horses in your games has distinct advantages when it comes to the marketability of your game:

The audience of horse lovers is hungry for content, and eager to try new things. Through the TMQ communities, you have an easy way of reaching people that are specifically looking for games with horses in them.

Cute interactions and animations make for very marketable material: clips and gifs of adorable animal gameplay have a decent chance of getting seen and shared widely on platforms like Twitter and TikTok.

Horses in games aren’t by themselves a particularly remarkable USP, but you can absolutely make your horses stand out among other game mounts by taking inspiration from the horse game genre and bringing certain features to a broader gaming audience.

Additional details and unexpected depth are often appreciated by many players – as long as they are accessible and not over-complex. Many of the tips in this article will contribute to your game feeling overall polished, and that in turn increases your game’s overall appeal and marketability.

These claims come with the caveat that horse details won’t by themselves make a bad game good, and that there’s never a guarantee that the horse loving audience won’t find flaws in your product even if you do cater to them explicitly. Our audience is eager to try new things, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be uncritical or content with any horse gameplay they get. They are however, in my experience, often very eager to help and advise game creators on how to improve horse details.

Any More Questions?

Even in almost 4000 words, I’m only scratching the surface here about what you can do to get horses right or wrong in your games, but I hope this article can be an introduction for gamedevs who want to add horses to their project and haven’t thought about this topic in depth before. There’s a ton of room to make horses in games cooler and more interesting, regardless of whether you only tweak a few details for accuracy or want to go further in making this audience happy.

Remember that the TMQ Communities are always glad to give feedback and insights about horse representation in games and other media, and that you can freely join those communities, read along and ask for details.

And if you want detailed input on how to improve the horses in your game or how to tackle a specific feature or issue, you can always ask for advice by reaching out to me at alice@themanequest.com!